How to Protect Children From Predators

Experts suggest the best way to protect your child from online predators is to be involved in their digital lives (O’Donnell, 2021).

The reality is that many parents don’t know how much involvement is healthy.

Can or should we possibly read every text message they send, view every TikTok they watch, and monitor every online chat they have? Why not ban all electronic devices from our homes?

Being involved in our kids’ digital lives doesn’t require us to be detectives, police officers, or dictators. It involves a handful of consistent things.

Four Ways to Be Involved in a Child’s Digital Life

Types of Online Predators

Sexual predators are those who use abusive methods, like deceit and coercion, to have sexual contact with another person.

Not all perpetrators prey on children, but nearly half of the 904,000 convicted sexual offenders in the U.S. are child sex abusers (Stathis & Marinakis, 2020).

Online child predators can be divided into several types, and being aware can help parents, educators, and caregivers protect young people.

Fantasy-driven predators

Some predators are “fantasy-driven” (de Santisteban et al., 2018, p. 204). This type never attempts to meet their victims in person and engages solely in online sexual behaviors.

Among their tactics are engaging in sexual conversations, exchanging explicit media, or having cybersex via webcams (Briggs et al., 2011, p. 85).

These predators use “control, [digital] permanence, blackmail, re-victimization, and self-blame” (Jonsson et al., 2019).

In a 2018 study, researchers learned that when children are victims of online abuse, the impact on their emotional and mental health is significant (Jonsson et al., 2019).

4 out of 5

children victimized online suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder

Contact-driven predators

Other predators are “contact-driven” (de Santisteban et al., 2018, p. 204).

These offenders are motivated to set up in-person meetings and have actual physical relationships (Briggs et al., 2011, p. 85).

According to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, “sextortion” is often used to coerce children to meet the online predator in-person.

These criminals ask for nude texts from their victims (as young as 8-years-old) and then threaten to distribute these images, unless the child agrees to meet in person.

These meetings often result in money being taken from the child or engaging in sex (National Center for Missing & Exploited Children. (n.d.).

Child pornography: Consumers, distributors, & producers

These types of predators are interested in making a profit from exploiting children.

It is currently not known the percentage of children who are found online and subsequently abducted with the intent of producing and distributing child pornography.

However, “FBI investigations indicate child abductors can use social media, social networks, and dating applications to identify, initiate contact, and gain access to children prior to their abduction (Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2020).

How Do Online Predators Find Their Victims?

Over 60% of the time, online predators meet their victims in digital chat rooms (Cardei & Rebedea, 2017, p. 590).

These chat rooms don’t have to be dedicated websites; they might be features within online games or social networks, as was the case for this mom’s daughter.

Predators will generally observe chats and gather information before choosing their victims (Greene-Colozzi et al., 2020, p. 839).

They search for minors who bring up topics related to sex, children who seem “needy” or “submissive”, and users with sexual usernames or profile pictures (de Santisteban et al., 2018, p. 204-205).

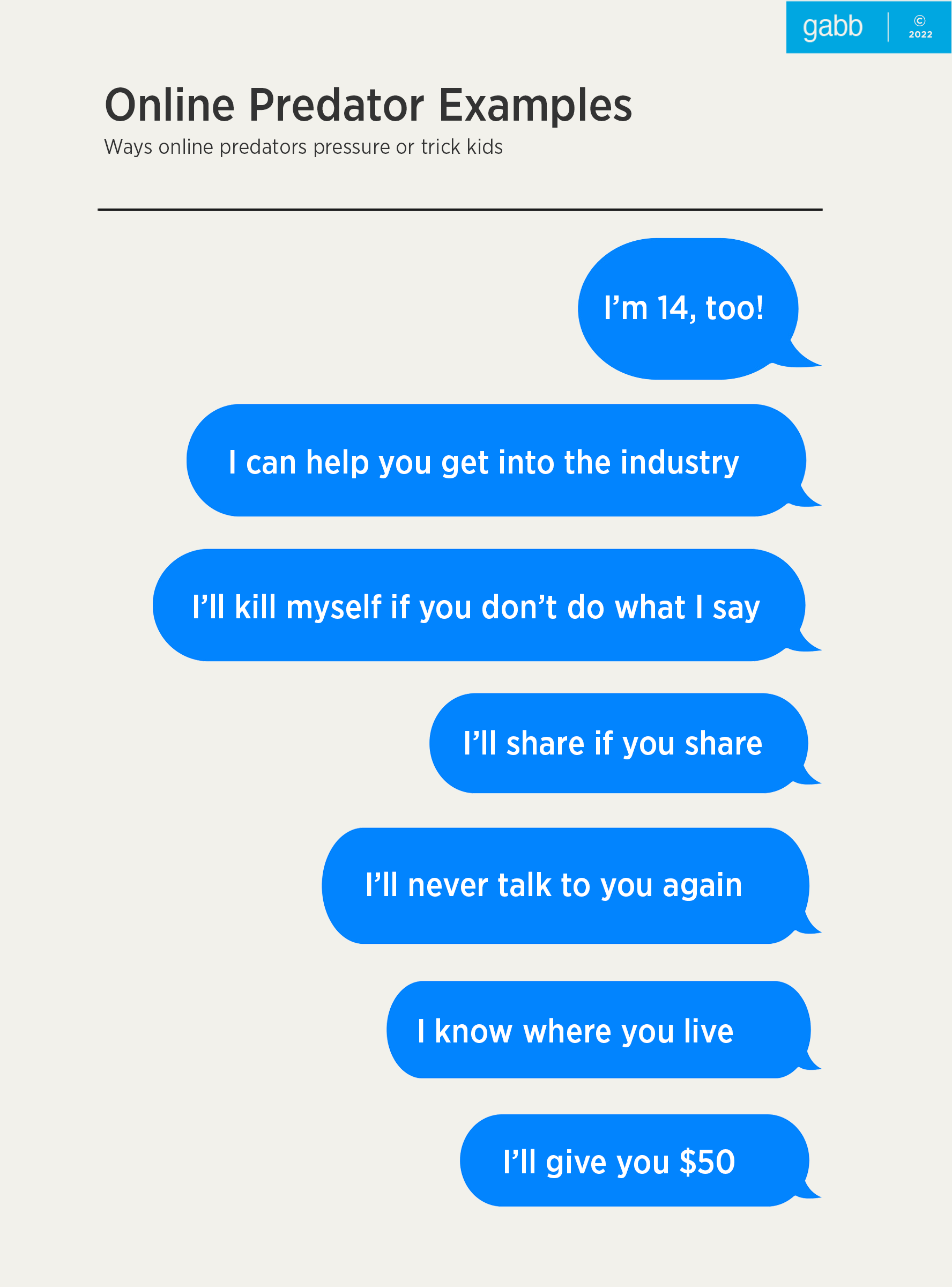

Online Predator Examples

- Express interest in the child’s hobbies (“You like cooking, too?”)

- Flatter the child (“You are literally the coolest person I’ve ever talked to on chat!”)

- Mirror the child’s emotions and language (“I know exactly how it feels to be mad at your mom.”)

(Greene-Colozzi et al., 2020, p. 839; Webroot, n.d.)

Online Predator Tactics

As parents, we often imagine online predators as shady figures pretending to be kids to gain access to young children. While this does happen, it typically isn’t the case.

Online predators usually readily admit they are older men.

In the vast majority of Internet sex crimes against young people, offenders do not actually deceive youth about the fact that they are adults who have sexual intentions.

They don’t hide that they are interested in a sexual relationship with adolescents (Wolak et al., 2013, p. 5). Instead, they prey on children’s insecurities or interests in romance, sex, or adventure (Crimes Against Children, n.d.).

How Predators Behave Online

- Do not lie about their age

- Don’t hide they are interested in sex

- Do notice and prey upon a child’s insecurities

- Do take time to assess a child’s profile

- Do target kids who are lonely, curious, reckless, or rebellious

Most predators seek out willing victims—adolescents who agree to have sexual relations. These kids tend to be lonely, curious, reckless, or rebellious.

Only 5% of physical meetings involve violence, and up to 50% of victims report being in love or in a relationship with their abuser.

While 16% of cases involved coercion or pressure from the predator, these abusers are generally charged with “nonforcible sexual relations with victims too young to consent” rather than forcible ones (Wolak et al., 2013, p. 2-3).

Offenders seduce youth by being understanding, sympathetic, flattering, and by appealing to young people’s interest in romance, sex and adventure.

—Crimes Against Children Research Center

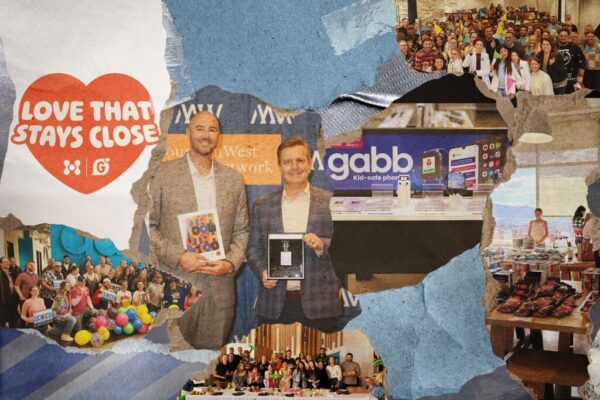

What are Deepfakes?

Deepfakes are videos, images, and/or audio of a person generated using artificial intelligence (AI) in which their face or body has been digitally altered so that they appear to be someone else, typically used maliciously or to spread false information.

Deepfakes are becoming increasingly sophisticated and easy to produce, with multiple free apps making this dangerous technology accessible to children and predators.

Predators use deepfakes to obscure their intentities online.

Predators may also pull from a child’s public online postings to create deepfake content showing a child doing or saying things they never did in real life. This content can be so convincing, it can be used to scam, extort, or manipulate a child.

How to spot a deepfake

- Audio: If the lips do not seem in sync with what the person is saying, it could be a deepfake. This is because the current AI struggles to match audio and lip movements correctly. Any audio that sounds robotic or unnatural should be a red flag.

- Eye Movements: In real videos, people have consistent eye movement and blinking. If you are watching a video with very few or unnatural eye movements, including blinking that seems contrived or mechanical, it’s an indication the video is fabricated.

- Lighting: In every image or video we take, the lighting is distinct. When multiple images/videos with various lighting sources are stitched together by AI, the results can seem off to a viewer. Listen to your instincts—it could be a fake.

Parents can teach children to trust their intuition—if online content seems off in any way it could be fake. Explain the consequences of creating deep fake content for others, even if it seems fun and harmless.

We can require young people to keep social media accounts private to reduce the chances of their images or videos being fabricated into deep fake content.

Protecting Our Kids

While this does not decrease the severity of the perpetrators’ crimes in any way, it changes the way we should approach protecting our children.

Rather than warning kids about online strangers kidnapping them, we can teach them differently.

Help them understand that exploring curiosity about sex is never safe with a stranger. Hyper-focusing on naive romantic fantasies, or succumbing to pressure from friends to become sexually active can make teens more vulnerable to online predators seeking to exploit children (Crimes Against Children, n.d.).

Kids Most at Risk From Online Predators

One in five youth have encountered unwanted sexually explicit material online, and one in nine have received online sexual solicitations (Madigan et al., 2018).

While some of these solicitations come from peers, one in twelve children is sexually exploited by an older person (Cardei & Rebedea, 2017, p. 590).

Certain kids are more at risk than others for sexual victimization

For example, girls are more likely than boys to receive sexual solicitations online, as are boys who are gay or are questioning their sexual orientation (de Santisteban et al., 2018, p. 204).

Youth with a previous history of abuse, a poor relationship with their parents, or a record of troubled behaviors are also at greater risk (Wolak et al., 2013, p. 5).

Further, certain behaviors lead to higher chances of unwanted sexual solicitations or exposure, such as engaging in risky offline behaviors or downloading files from file-sharing programs (Wolak et al., 2013, p. 5).

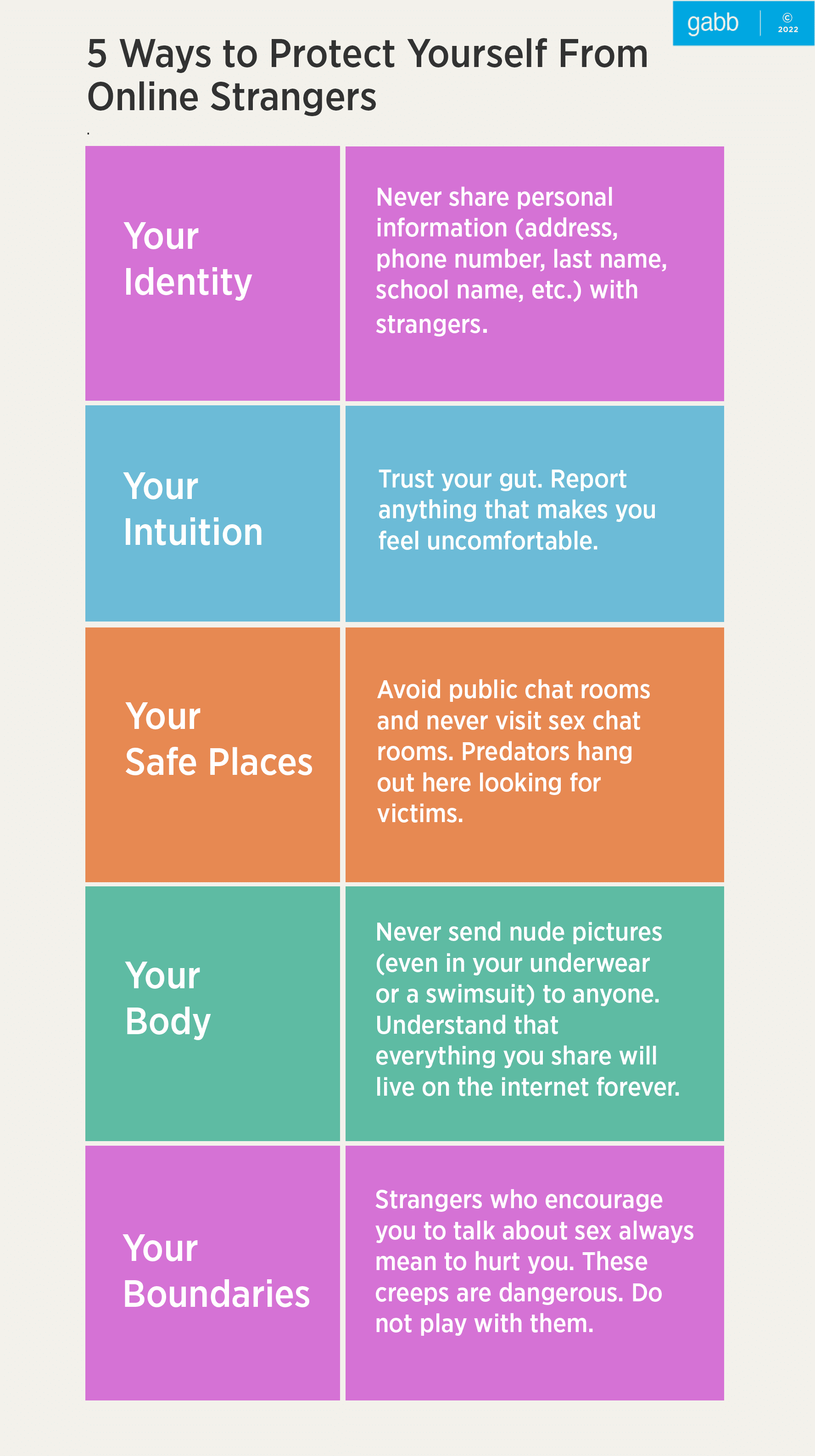

We can empower our kids to keep themselves safe the next time they encounter an online predator. As caregivers and parents, we can be a safe place to discuss this contact.

7 Ways for Kids to Protect Themselves from Online Predators:

- Ignore Direct Messages (DMs) from strangers

- Don’t talk to strangers online or share personal information

- Avoid having unknown friends or followers

- Stay away from sexually explicit sites

- Never talk to strangers about sex

- Don’t use a provocative profile picture or username

- Always put your device down and talk to an adult if you’re unsure about someone

Reviewing these tips regularly is an important step in developing media literacy.

Consider printing these safety guidelines and posting them next to a home computer.

Dangers of Online Predators

Online predators are dangerous, even though they may never make in-person contact with our children.

In online spaces, they can groom, sexually abuse through sharing explicit content, misguide, coerce, threaten, and harass kids online.

But there are other ways they can harm families, such as damaging mental health and sextortion.

Mental health effects of online predators

In a recent study discussing the effects of interactions with online predators, we see this contact often negatively affects youth mental health.

In fact, 25% of kids who received online solicitations said it was psychologically distressing (Madigan et al., 2018, p. 134).

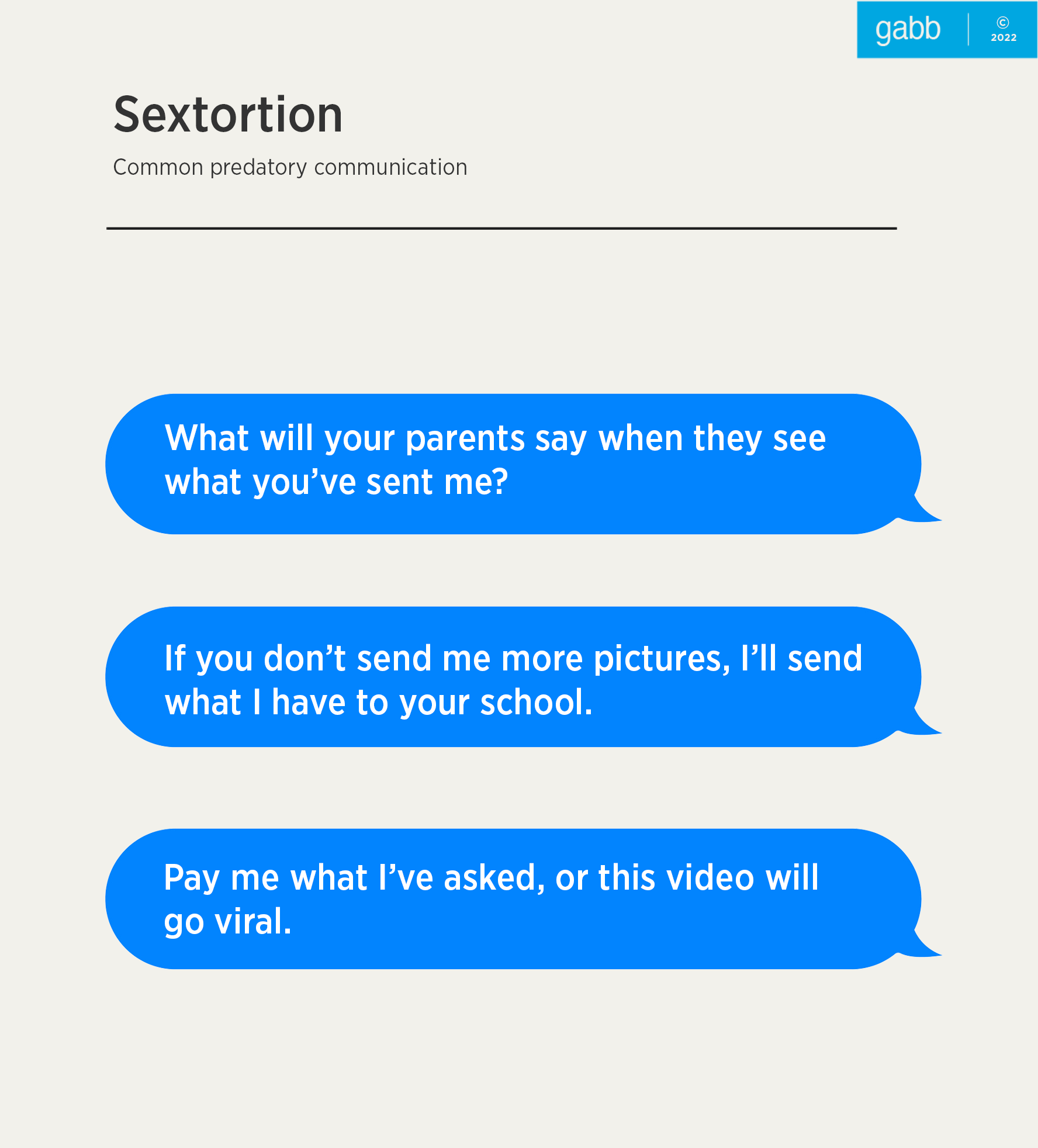

Sextortion

The definition of child sextortion is using a child’s sexual activity to obtain money or sexual favors.

After contacting their target, predators will attempt to move their conversations into more private venues (private video calls or instant messaging services).

Here, they pressure the child to send nude pictures, engage in cybersex, or talk about their sexuality.

Children and adolescents do not understand the notion of digital permanence and are vulnerable to these tactics.

These degenerates will then use any evidence they have collected (compromising photos and videos, admissions to diverse sexual orientations, etc.) to pressure children into giving them money or sharing more sexually explicit photos or videos.

They might tell the child, “If you don’t send me more pictures, I’ll send what I have to your school.”

Children feel uncomfortable and can be forced to engage in increasingly harmful behavior to avoid the predator’s threats.

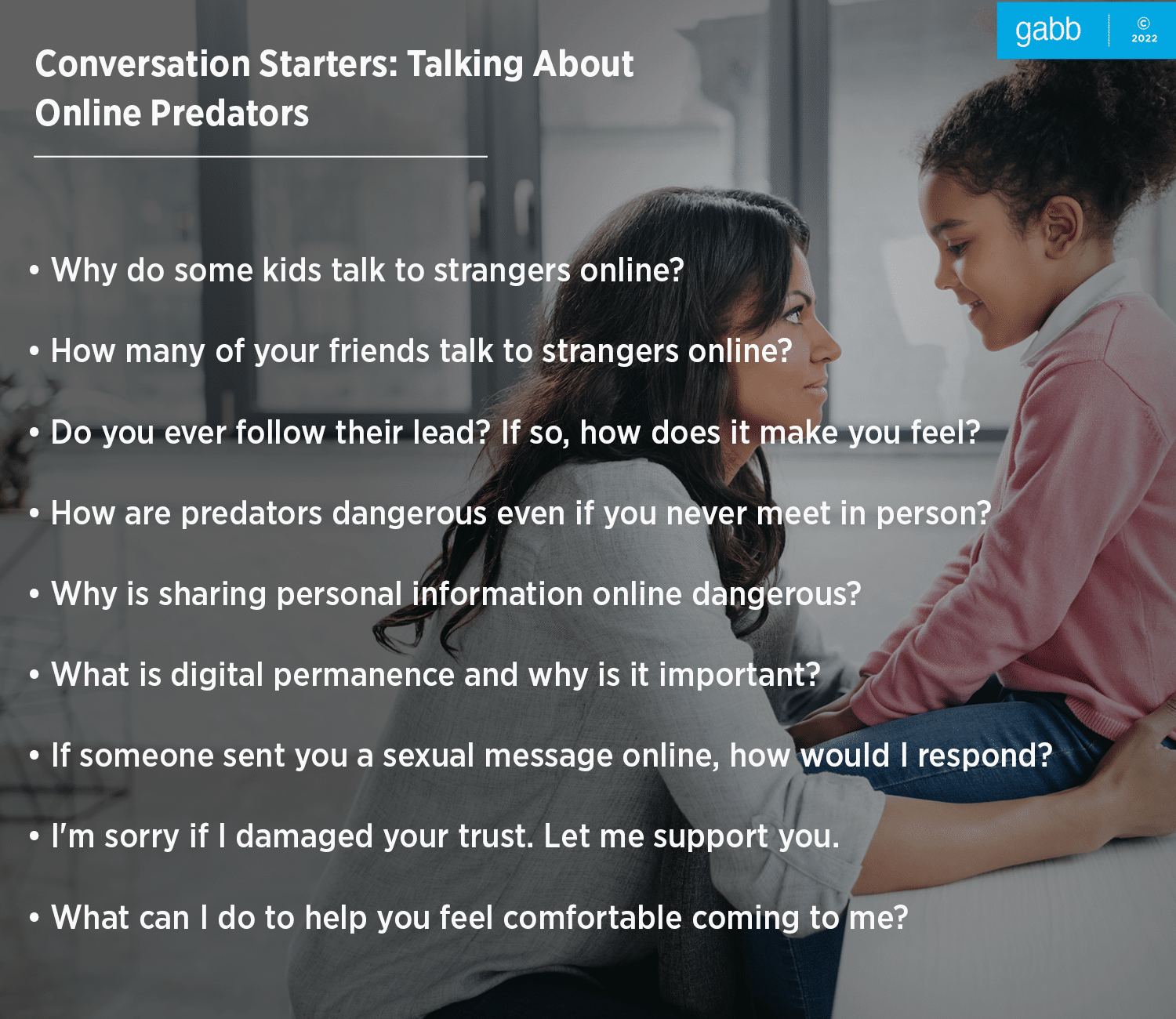

How to Talk to Our Kids About Online Predators

To protect our children from online predators, their tactics, and the dangers they pose, it is important to continually discuss these things with our kids. Since 25% of online victims are 13 years old, these conversations must begin at ten or eleven (Wolak et al., 2013, p. 8).

Talk about healthy relationships

Our children need to hear about the dangers of forming intimate relationships with online strangers, including sextortion and coercion.

They need to be aware of predators’ tactics to meet and manipulate their victims.

We need to talk to them about online safety, especially the principle of digital permanence—that video calls can be secretly recorded and even privately sent pictures can be posted and reposted online, even if they use Snapchat (Wolak et al., 2013, p. 8).

Children must learn that sexual relationships between adults and youth are dangerous and illegal, even when conducted completely online.

In addition, they need to understand that adults who encourage inappropriate relationships are usually involved in multiple relationships, and that caring adults will never ask for sexual favors from them (Wolak et al., 2013, p. 8).

Express support

Finally, our children need to know we are always there for them. We need to build their trust that if they have an issue, we won’t ‘freak out’.

It is important to understand that victims of sexual predation and sextortion are not at fault for what has happened to them, regardless of decisions they made. Let them know that they will be supported.

Safety Tips

No parent can completely protect their child from being approached by an online predator, but there are ways we can prepare our kids to protect themselves when it happens.

Providing children with a safe device that is not connected to the internet eliminates the need for parental controls.

If children do have a smartphone, even with parental controls, predators constantly look for ways to make contact.

Having internet safety guidelines for kids and teens in place will help kids know exactly what to do when a stranger attempts to make contact with them online.

References

- Briggs, P., Simon, W. T., & Simonsen, S. (2011). An exploratory study of internet-initiated sexual offenses and the chat room sex offender: Has the internet enables a new typology of sex offender? Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 23(1), 72-91

- Cardei, C., & Rebedea, T. (2017). Detecting sexual predators in chats using behavioral features and imbalanced learning. Natural Language Engineering, 23(4), 589–616

- Crimes Against Children Research Center. (n.d.). Internet Safety Education for Teens: Getting It Right. University of New Hampshire. http://unh.edu/ccrc/internet-crimes/safety_ed.html

- Gámez-Guadix, M., Almendros, C., Calvete, E., & De Santisteban, P. (2018). Persuasion strategies and sexual solicitations and interactions in online sexual grooming of adolescents: Modeling direct and indirect pathways. Journal of Adolescence, 63, 11–18

- Greene-Colozzi, E. A., Winters, G. M., Blasko, B., & Jeglic, E. L. (2020). Experiences and perceptions of online sexual solicitation and grooming of minors: A retrospective report. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse: Research, Treatment, & Program Innovations for Victims, Survivors, & Offenders, 29(7), 836–854

- Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2020, October 15). Internet crime complaint center (IC3): Child abductors potentially using social media or social networks to lure victims in lieu of an in-person ruse. Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3) | Child Abductors Potentially Using Social Media or Social Networks to Lure Victims In Lieu of an In-Person Ruse. Retrieved March 20, 2022, from https://www.ic3.gov/Media/Y2020/PSA201015

- Jonsson, L. S., Fredlund, C., Priebe, G., Wadsby, M., & Svedin, C. G. (2019, August 24). Online sexual abuse of adolescents by a perpetrator met online: A cross-sectional study - child and adolescent psychiatry and Mental Health. BioMed Central. Retrieved March 20, 2022, from https://capmh.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13034-019-0292-1

- Madigan, S., Villani, V., Azzopardi, C., Laut, D., Smith, T., Temple, J. R., Browne, D., & Dimitropoulos, G. (2018). The prevalence of unwanted online sexual exposure and solicitation among youth: A meta-analysis. Journal of Adolescent Health 63(2), 133-141

- National Center for Missing & Exploited Children. (n.d.). Sextortion. Home. Retrieved March 20, 2022, from https://www.missingkids.org/theissues/sextortion

- O’Donnell, B. (2021, February 24). Rise in online enticement and other trends: NCMEC releases 2020 exploitation stats. National Center for Missing & Exploited Children. Retrieved March 15, 2022, from https://www.missingkids.org/blog/2021/rise-in-online-enticement-and-other-trends--ncmec-releases-2020- de Santisteban, P., del Hoyo, J., Alcázar-Córcoles, M. Á., & Gámez-Guadix, M. (2018). Progression, maintenance, and feedback of online child sexual grooming: A qualitative analysis of online predators. Child Abuse & Neglect, 80, 203–215

- Stathis, M. J., & Marinakis, M. M. (2020). Shadows into light: The investigative utility of voice analysis with two types of online child-sex predators. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse: Research, Treatment, & Program Innovations for Victims, Survivors, & Offenders, 1-21

- Wolak, J., Evans, L., Nguyen, S., & Hines, D. A. (2013). Online predators: Myth versus reality. New England Journal of Public Policy, 25(1), https://scholarworks.umb.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1646&=&context=nejpp&=&sei-redir=1&referer=https%253A%252F%252Fscholar.google.com%252Fscholar%253Fhl%253Den%2526as_sdt%253D0%25252C45%2526q%253Dtypes%252Bof%252Bonline%252Bpredators%2526btnG%253D#search=%22types%20online%20predators%22

Success!

Your comment has been submitted for review! We will notify you when it has been approved and posted!

Thank you!